The Chinese Economy: Key China GDP Indicators and Recent Trends

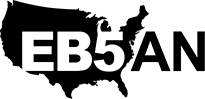

Although 2015’s GDP represents a significant slowdown in China’s economy compared to the historical trend and is somewhat worse than 2014’s 7.4%, this slowdown was not unexpected. It will be interesting to see whether this figure gets revised in the coming months and whether the revision is up or down.

On the positive side, the components of GDP show that consumption is now 66.4% of the economy. Most observers have thought that China would indeed become a consumption driven economy (because this has been part of the Five Year Plans for a decade now), but few were expecting this change to occur so quickly.

Another bright spot was how the GDP growth rate of 6.9% shows that more than half of that growth came from services (i.e., the tertiary economy). On the surface, that’s great news since it backs up the consumption growth trend, but this shift has also happened in a relatively short time span.

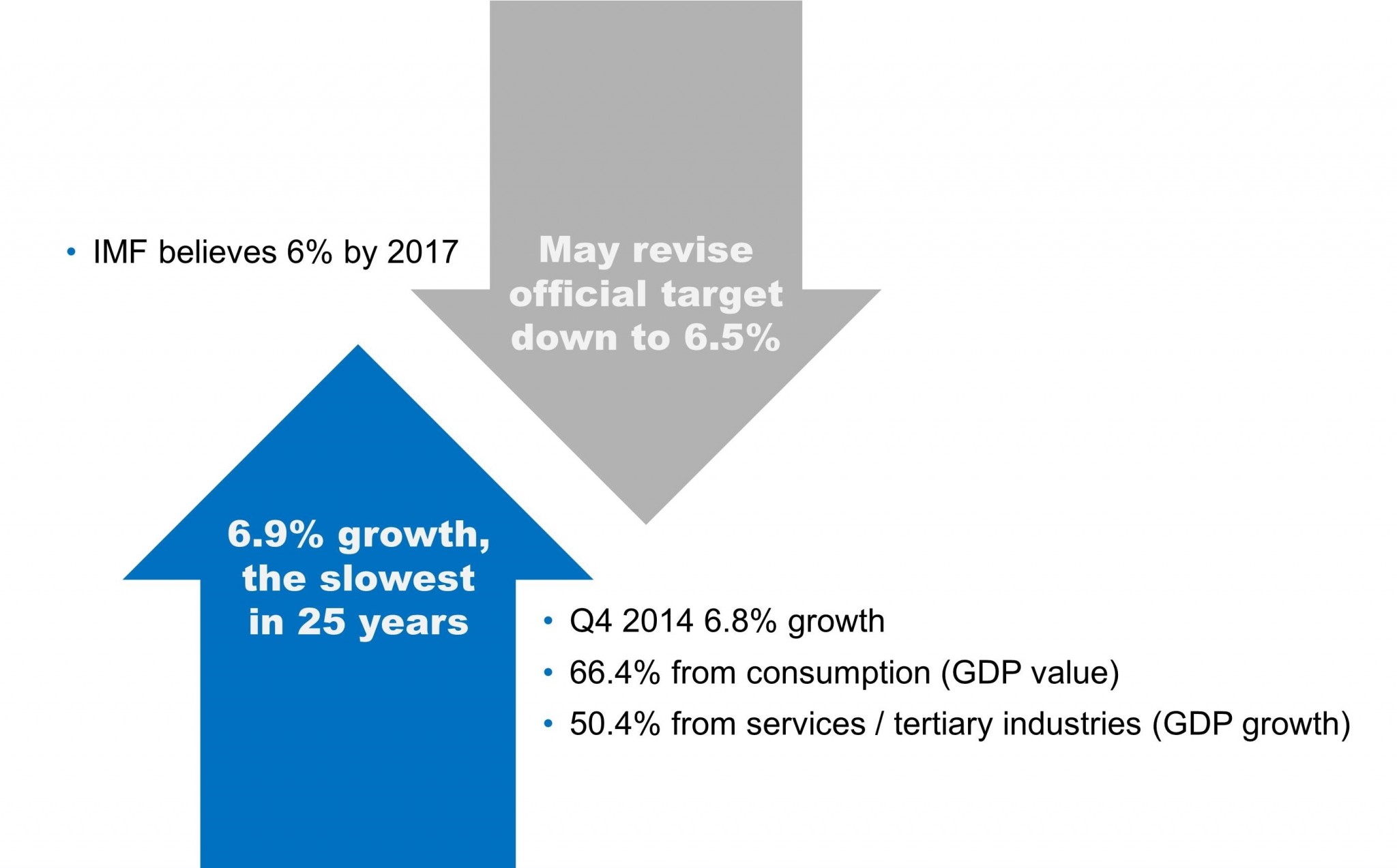

Analysis of China’s GDP figures should always be tempered with some GDP proxies. The big proxy of the past few years, ever since the so-called Li Keqiang Index started to be followed, is electricity production. We see that the divergence between electricity production and growth became even greater in 2015. What does this mean?

Well, this widening gap could be explained by the growth in consumption and services, which use less electricity per unit of GDP than industry. Or it could mean that Chinese companies have become much more energy-efficient. Or it could indicate some problems in the data that may come out when revisions are announced in the coming months.

Many economic analysts now discount the use of the Li Keqiang Index as a remnant of China’s more traditional investment- and manufacturing-driven economy. New GDP proxies can be a useful substitute, especially if they primarily measure consumption and tertiary industries.

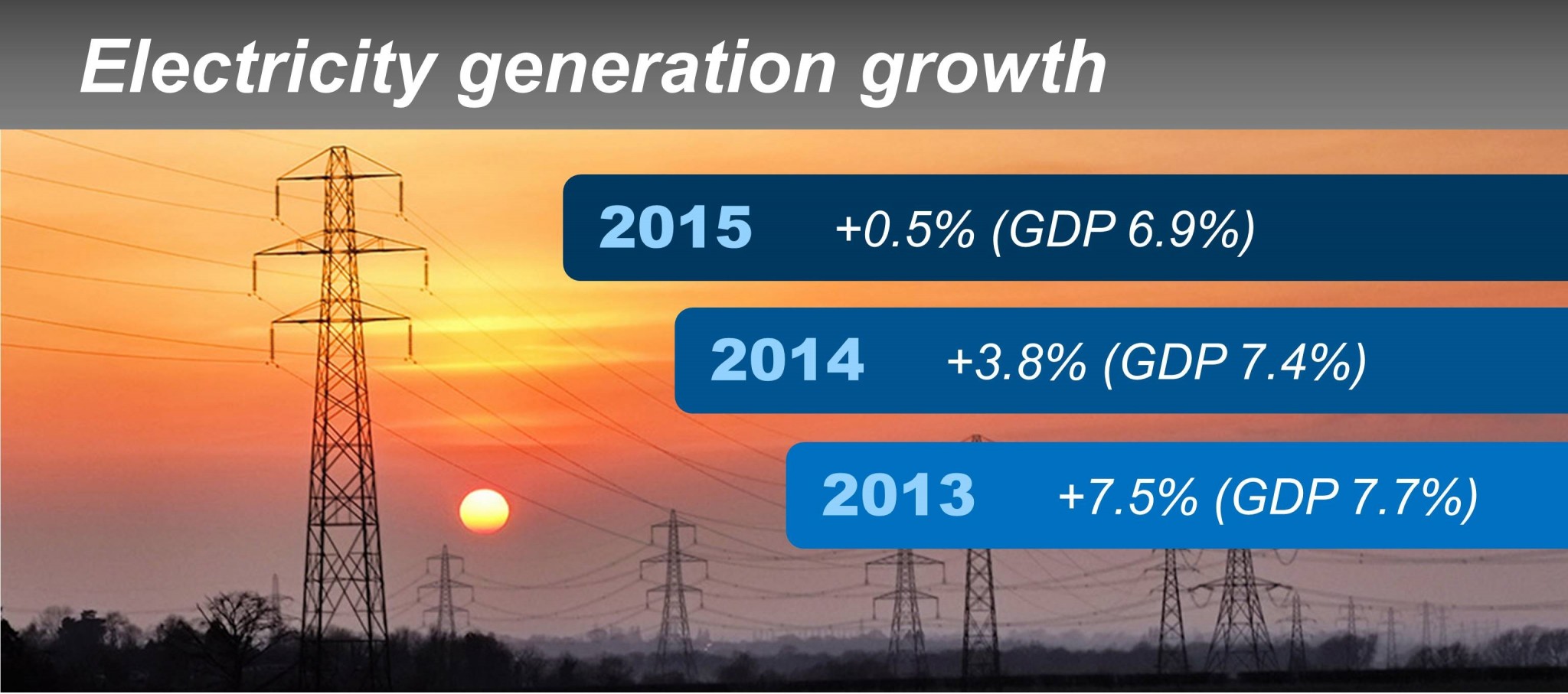

The data look good, with huge growth coming from eCommerce affecting the courier industry, as just one example. Alibaba and other eCommerce platforms and sellers saw more packages delivered than ever before. And couriers appear to be getting more productive, delivering more packages for less revenue.

Movie Box Office Sales

Box office sales were big in China last year, and they are going to be bigger this year simply because more screens are being opened and consumers have more movies to choose from. Hooray for Chollywood! This leads to our first prediction…

Kung Fu Panda 3 was released in China on January 29, and it’s going to achieve the biggest box office results of any movie this year. This prediction is based partly on the movie’s favorable release date just ahead of the Chinese New Year, but it is also partly due to the Sino-centric content, the fact the movie is a threequel of an already popular franchise, its cross-border star power from two Jacks (Jackie Chan and Jack Black), and, last but not least, its nature as an East-West co-production by the 2012-established joint venture Oriental DreamWorks, with their studio in Shanghai, and partners like China Media Capital (an investor in IMAX) and SMG. Go Po!

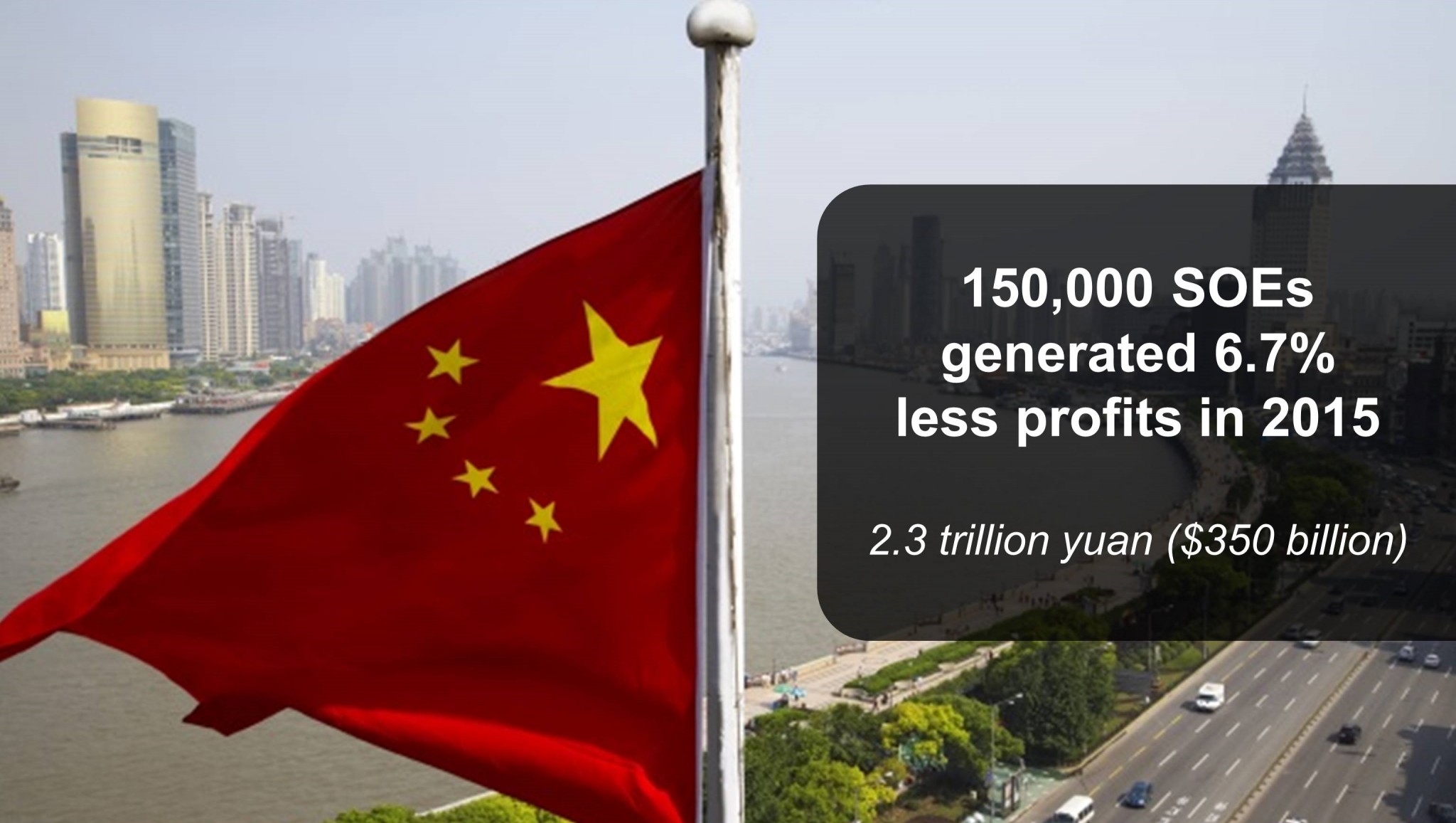

State-owned Enterprises

State-owned enterprise (SOE) reform is in the central government’s plan for the year for reasons that include the following: profits at SOEs, which partly accrue to the government as dividends and thereby support social services and the government’s budgets, are down by more than $20 billion from last year. This year’s take of $350 billion is nothing to sneeze at, but lots of analyses show that China’s SOEs are very inefficient, with ROEs significantly below private industry as just one indication. Bloated payrolls are another.

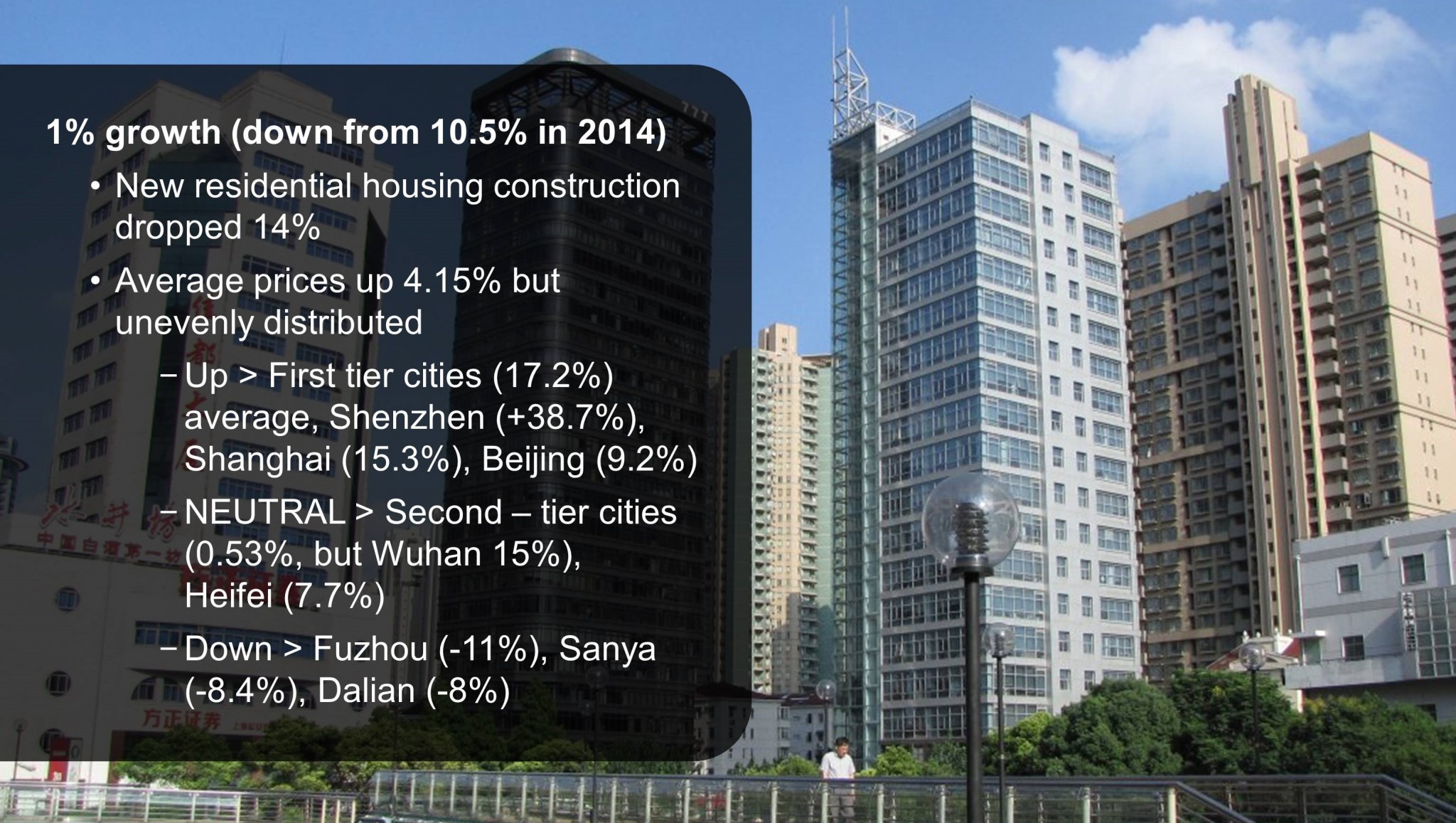

These real estate investment numbers pretty much speak for themselves. Property investment was, overall, not good in China in 2015. That said, the construction industry is not hurting as much as one might think: it is doing more projects abroad than ever before.

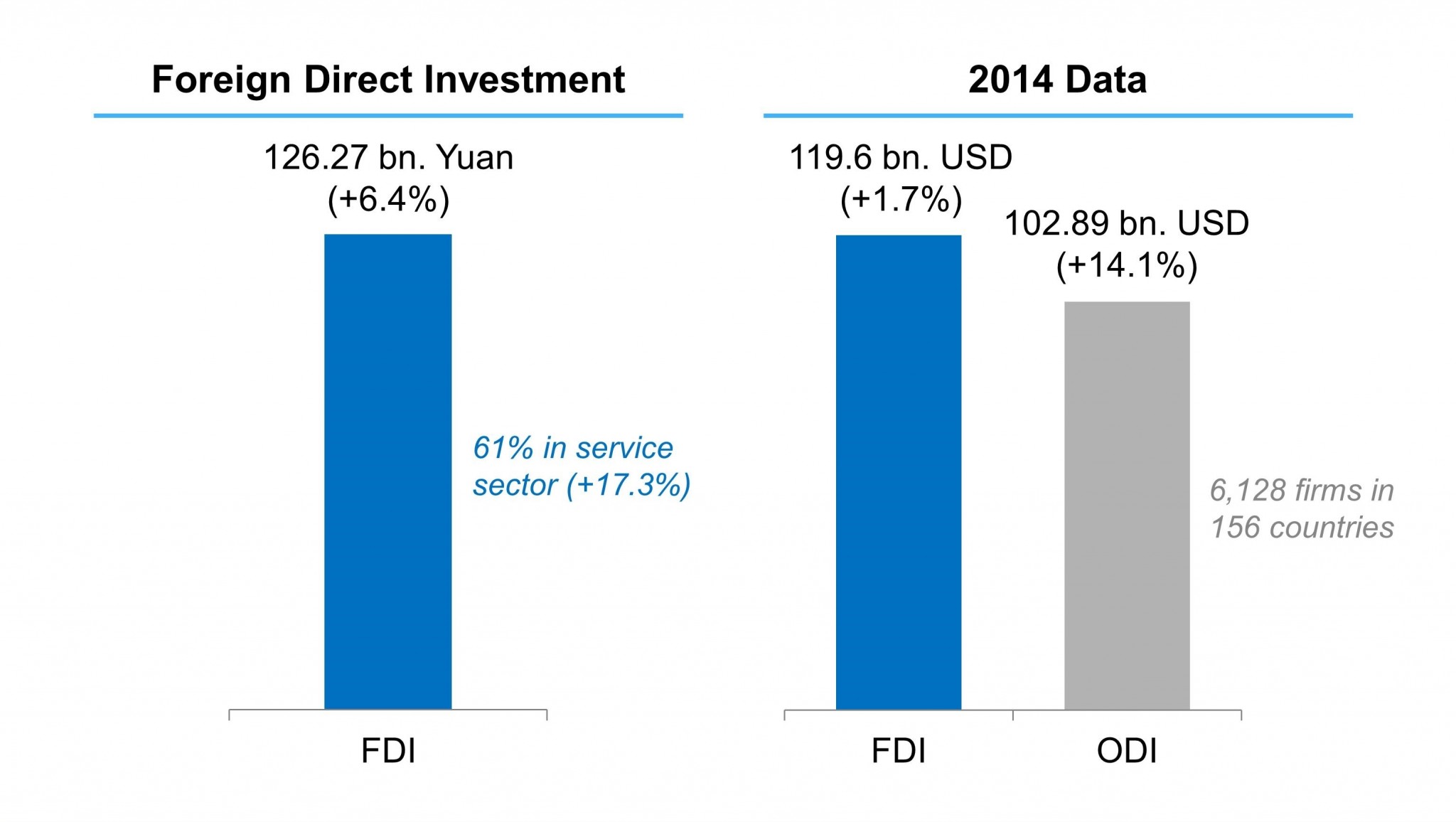

Foreign companies still find China an attractive investment. Note the faster growth in service-sector investments.

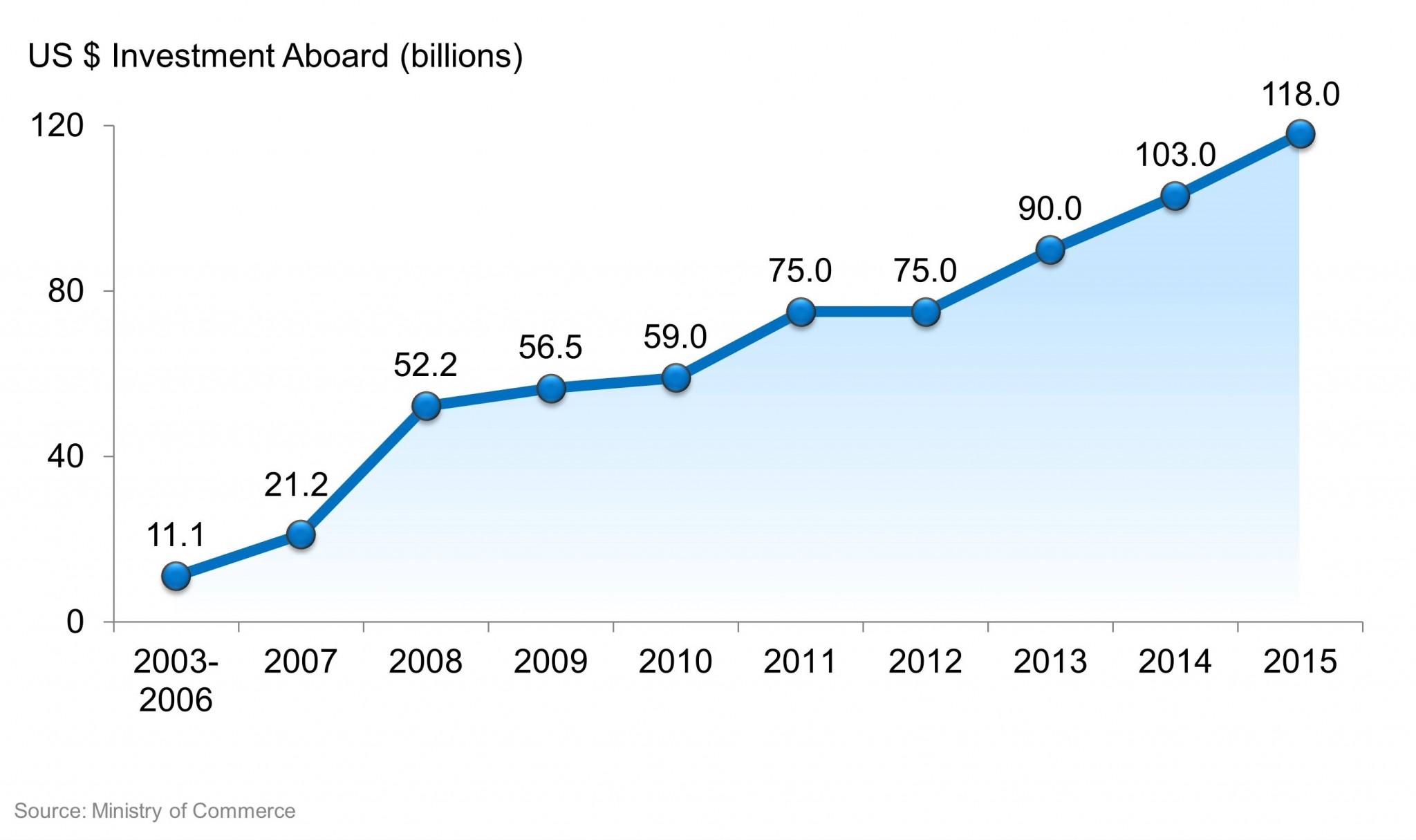

The bigger story was the continued growth in Overseas Direct Investment, which can be partly attributed to China’s…

This policy is not new; it has been talked about for at least the previous (12th) Five Year Plan and unofficially even before that. The policy is finally being executed in greater amounts and with greater speed.

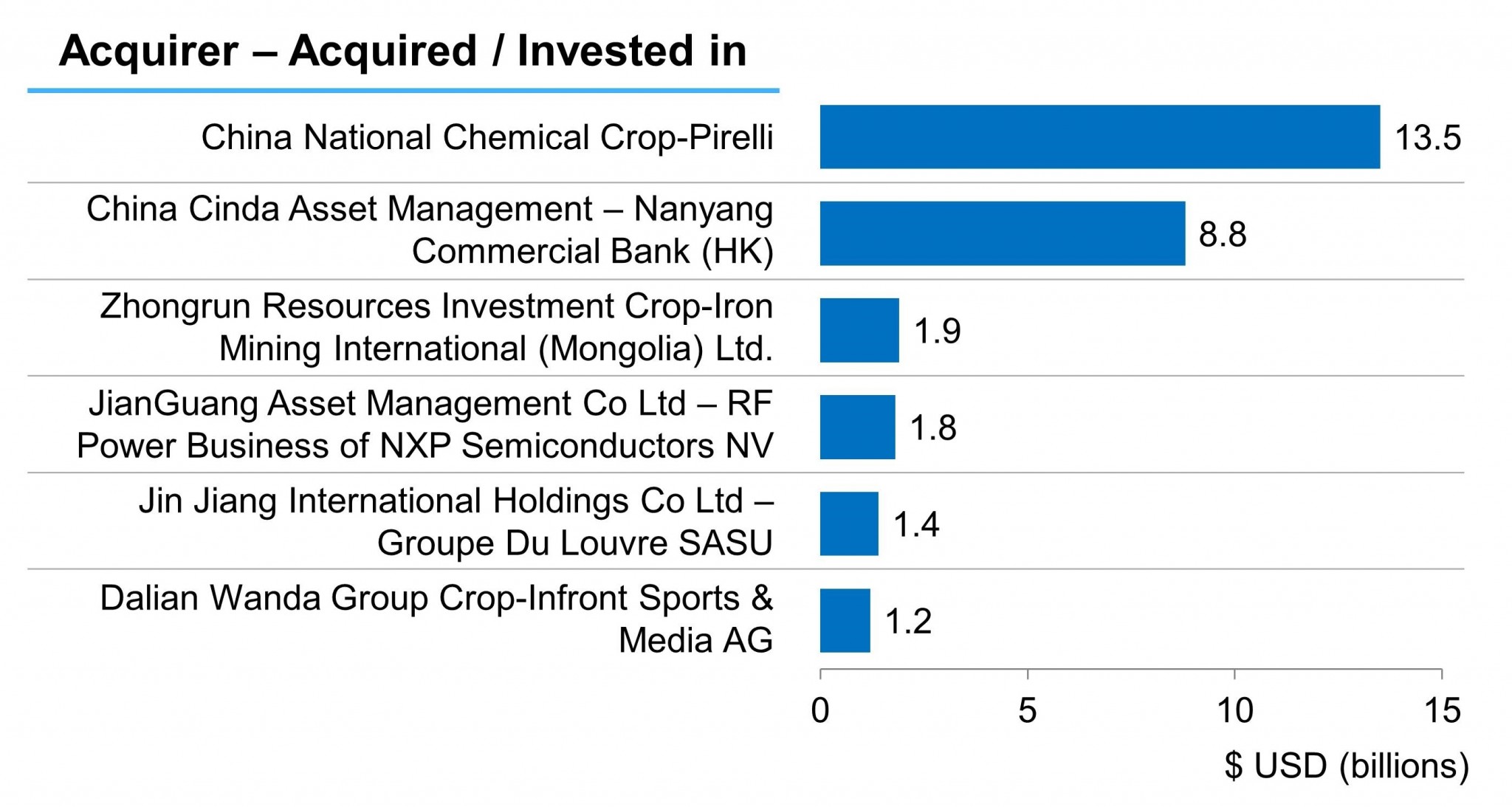

Among some of the big deals of 2015, China National Chemical Corp and Wanda are especially noteworthy, and these companies are likely to be 2016’s biggest acquirers in overseas M&A deals:

In January, these were still pending but are expected to go through. Sometime in 2016, a Chinese company will make an even bigger acquisition, in the $50+ billion range, signaling the nation’s companies are now major players, making 2016 a year in which China’s ODI will increase dramatically, perhaps to $180 billion.

Overseas Investments by Chinese Companies

Overseas investment is not just about M&A, it’s also about companies investing, building, and buying abroad. One of the big reasons 2016 will be a record year in ODI is that the New Silk Road, now known as One Belt One Road, is kicking into full swing, especially in the Middle East.

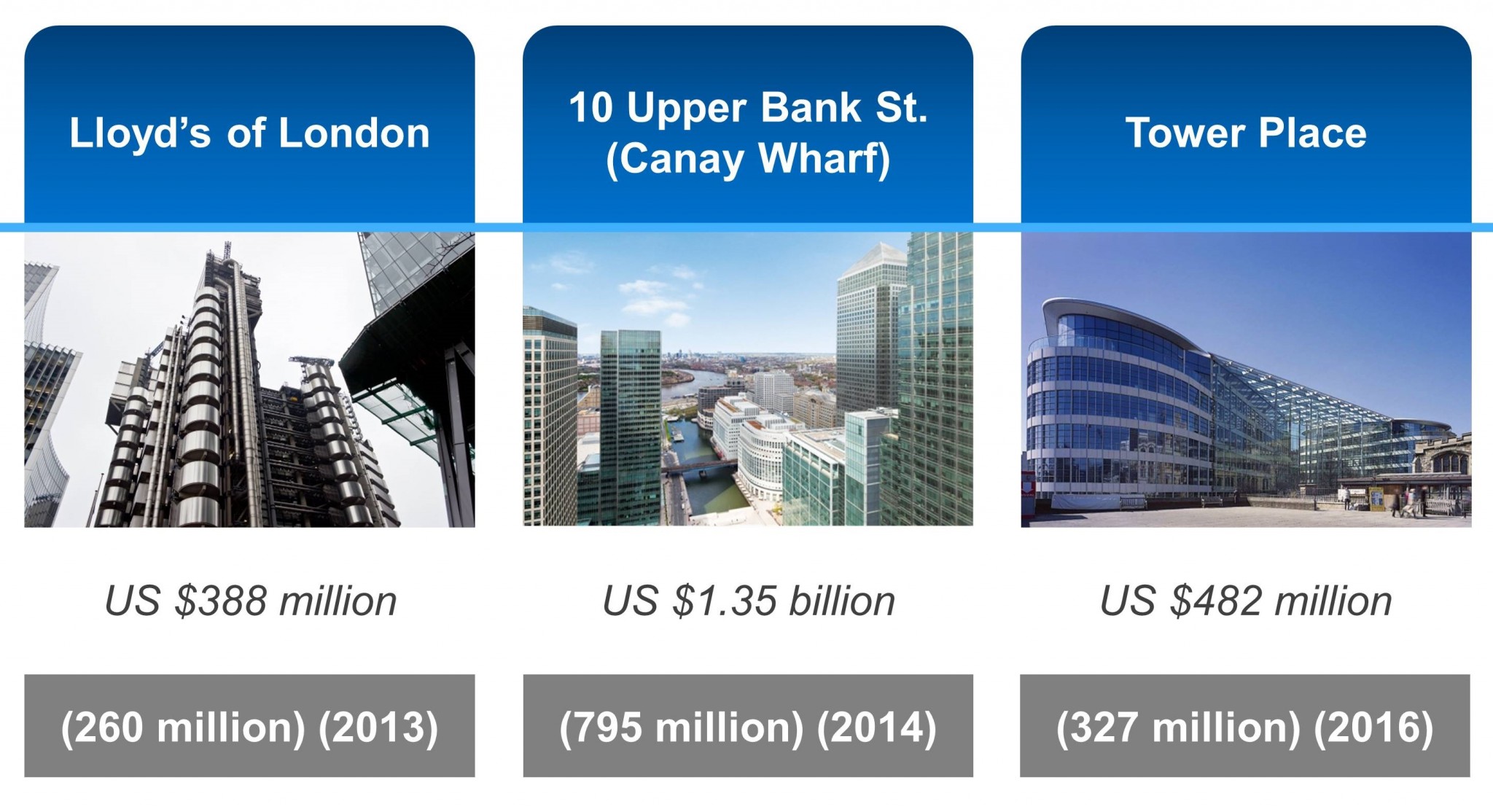

And real estate investment by China’s insurers is also part of ODI. China’s insurers made some big investments around the world over the course of the last two years, and such investments are also expected to rise in 2016.

China’s insurers love London in particular, it seems.

While not considered part of ODI, Chinese private investors are also buying numerous assets overseas, like this Modigliani, at a near-record-setting price of around $170 million by former taxi-driver Liu Yiqian. And, of course, Chinese individuals’ purchases of real estate in major cities like Sydney, London, and Vancouver continued in 2015. All of these investments abroad by Chinese companies and individuals led to a demand for foreign currency:

In 2015, China’s foreign exchange reserves decreased by a record amount, down to $3.33 trillion. But official reserves are just part of the story. Outflows of so-called hot money increased, and the day after our forum, a Bloomberg analysis put the total outflows for the year at an astonishing $1 trillion, far larger than earlier estimates.

Population and Workforce Demographic Changes

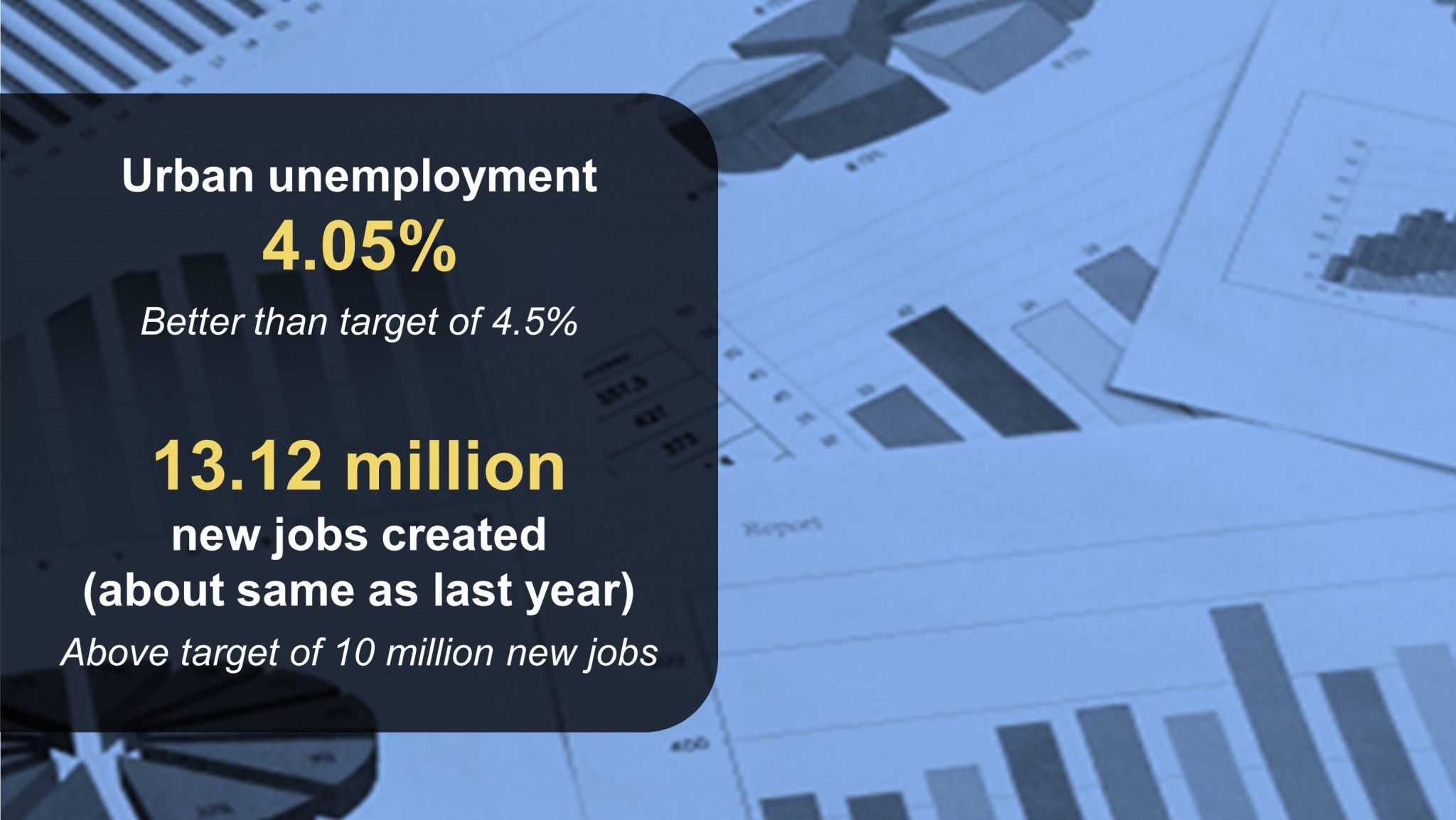

We haven’t talked much about demographic indicators, but job creation seemed healthy in 2015. Remember that China has about 7 million new higher-education graduates each year alone, plus all the people moving into the cities as part of China’s drive for urbanization. Some other demographic indicators could be considered along with this:

China’s workforce is shrinking quickly due to the nation’s ageing population. Many of those 4.87 million people might have been retired already (retirement age in China can be as early as 55), and retirement doesn’t necessarily mean their positions will be filled again (the SOE reforms in particular will use a lot of early retirements to reduce headcount). So many workers leaving the labor pool, however, is still bound to have some impact on wages and employment, but this is more of a long-term trend.

Furthermore, new births decreased by 300,000 despite the loosening of the Family Planning Policy. Whether rooted in superstition surrounding the year of the goat or whether because most people think raising a child, or a second child, is too expensive are questions for market researchers, but at the very least, this decreased birth rate is something to keep an eye on. Can China’s feng shui Year of the Monkey result in an increase in births? No prediction here, but remember a mini-baby-boom did happen in the Golden Pig year a few years ago.

Some 2016 policies, in particular easier Hukou registration, will likely see more people moving into cities—though it might be fairer to say many people were already in cities who hadn’t been able to get a Hukou before now.

The revision in the Family Planning Policy is now official. Every couple can now have two children. Long term, this policy will still result in a decrease in China’s population since having two children is slightly below the replacement rate (2.1 children per couple). Additionally, we cannot assume everyone eligible to have a second child would; last year’s decrease of 300,000 births demonstrates this reality.

Regarding entrepreneurship, it’s important to note that China’s job creation is going to be driven more and more by SMEs, so the government is putting large resources into supporting entrepreneurs, especially new graduates who want to jump right into a startup, This support will, it seems, include better access to loans:

Chinese Credit & Finance Markets

This credit growth might look good, but remember that China’s credit growth and debt-to-GDP levels are already approaching worrisome levels. Also, this figure is dominated by loans from the state-owned banks, and such loans are given in greater proportion to SOEs and large companies. This practice leaves entrepreneurs and SMEs scrambling for capital. Fortunately, business expansion can be financed in other ways:

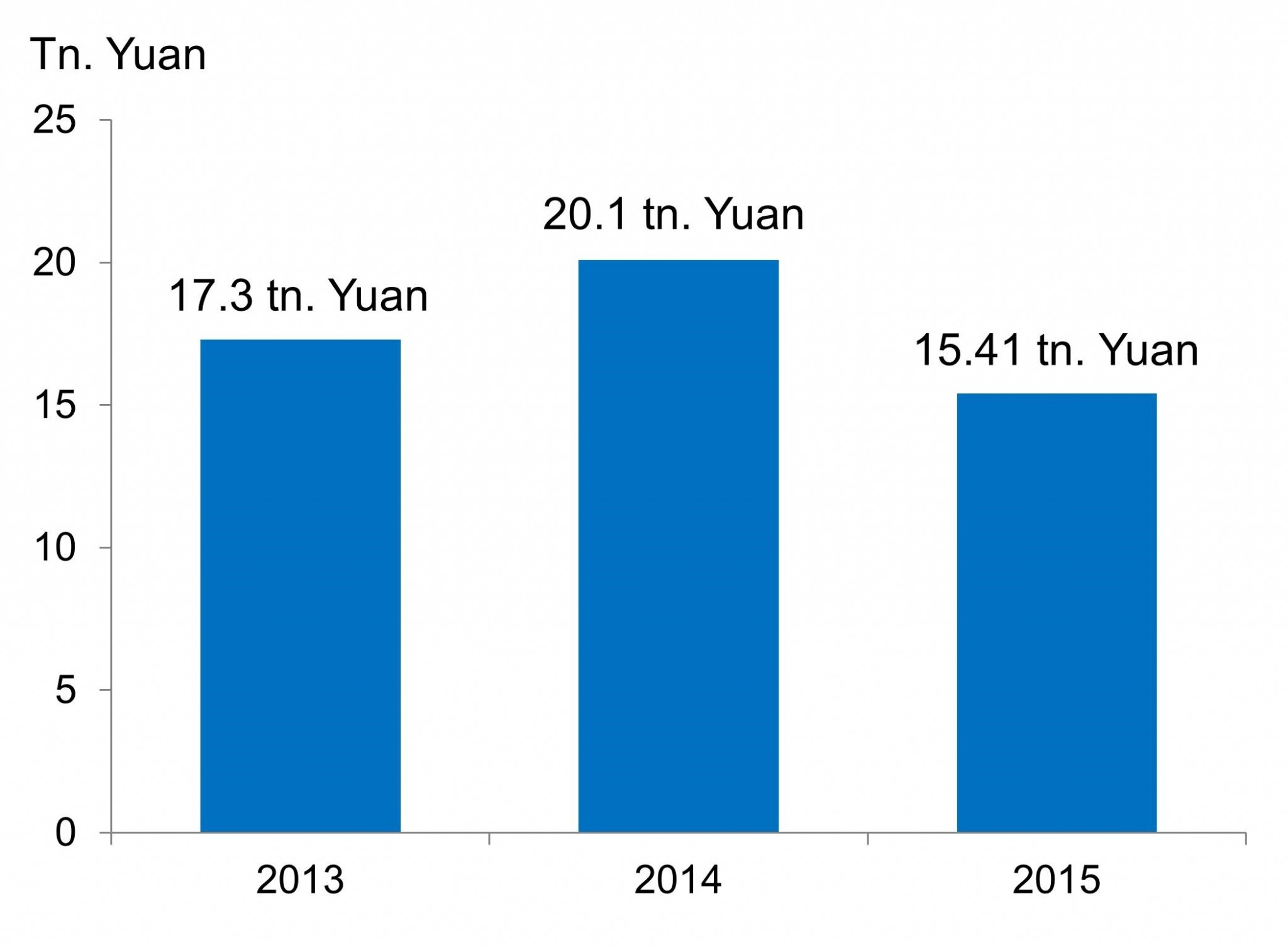

Unfortunately, alternative finance options decreased by a not insignificant amount of almost 5 trillion yuan last year. On the other hand, since Total Social Finance also measures a significant portion of the shadow-banking sector (trust loans at exorbitant interest rates), maybe the decrease is not such a bad thing. China’s shadow-banking sector has been growing too fast in previous years, and so this decrease might be a good sign of deleveraging in that risky sector.

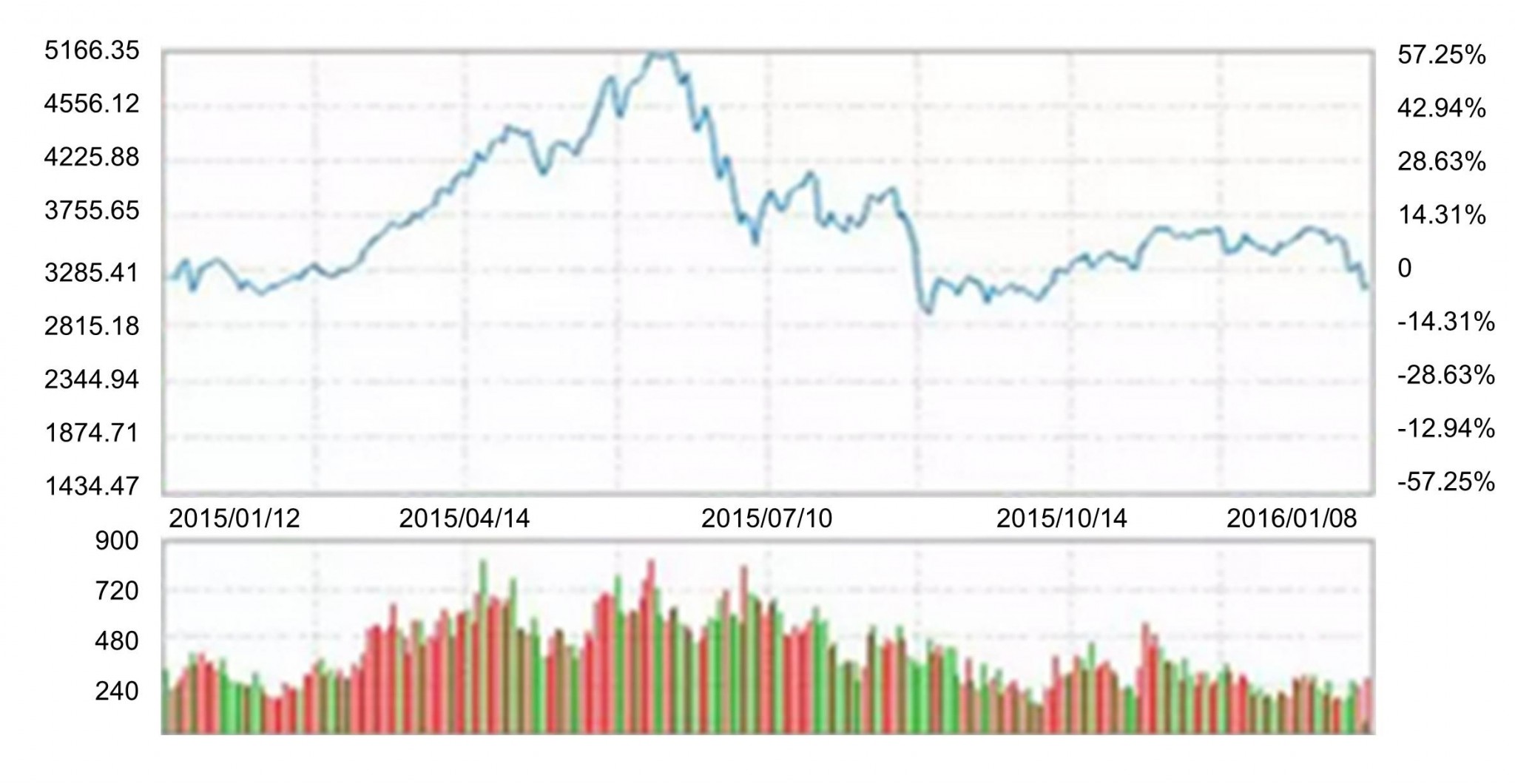

Another potential bad sign for consumption power is last year’s stock market performance, which pretty much ended where it started. Most investors in China are individuals rather than institutions, meaning that the wealth effect is operating in the negative. As a result, people are less likely to continue purchasing big-ticket items like cars, travel, and even housing, though in the past we’ve often seen an inverse correlation between property and stock markets.

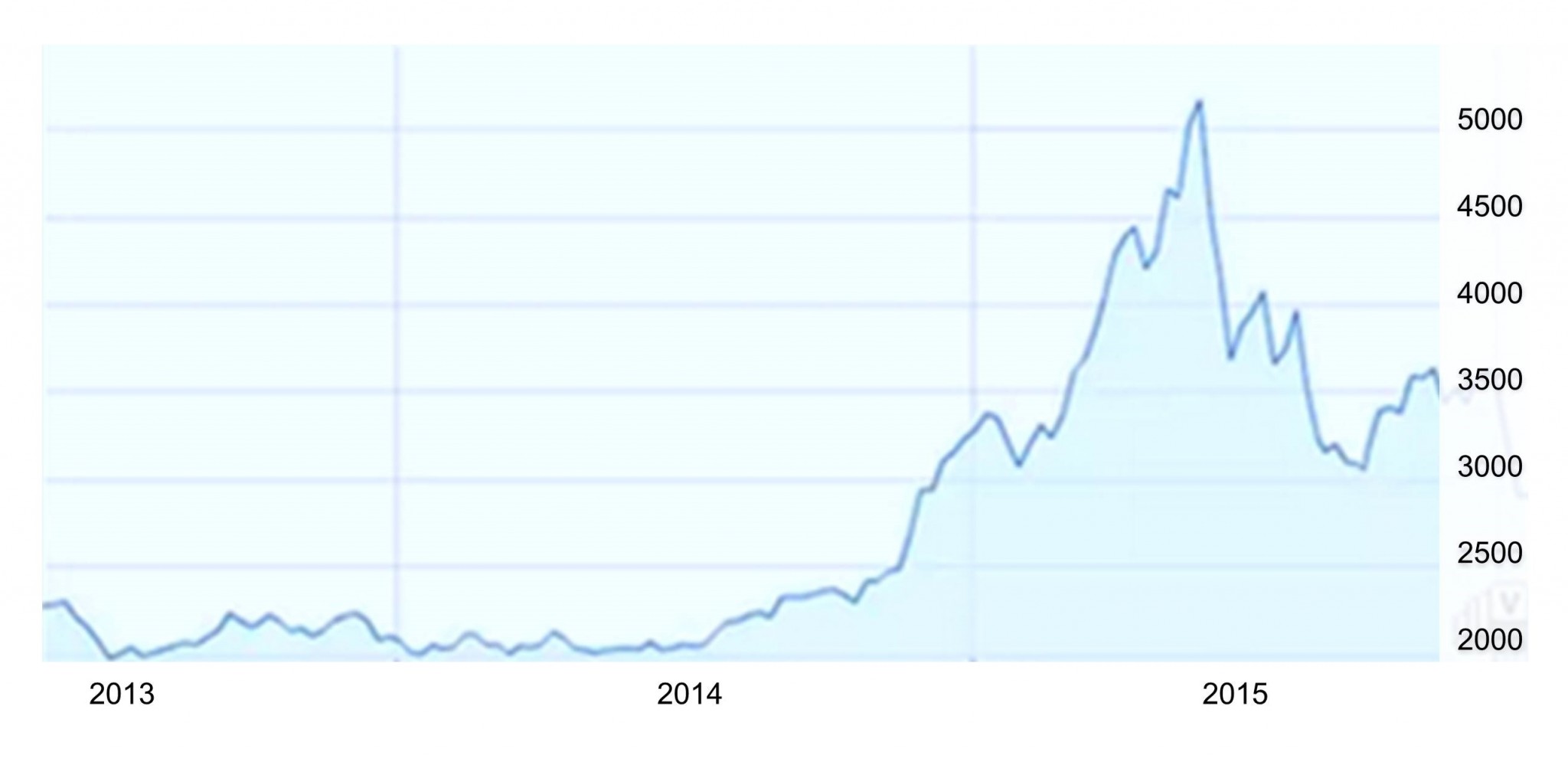

In other words, Chinese investors have traditionally put their money in stocks, then properties, then back into stocks, as each market rose or fell. If the same is true today, we can expect property markets to pick up in 2016. This year marked the deflation of China’s second equity bubble in the past ten years (the first being in 2007), but to get the full picture, look at the following three-year chart:

If you are a chart analyst, you might see a danger here of the market continuing to go down in 2016, possibly bottoming out at around the 2000–2200 point level, which is where it had been stuck for several years previously. Oh well—easy come, easy go? Still, such a decline is not a foregone conclusion, and China could still revitalize its stock markets in 2016 with the right policies:

The only other prediction for 2016 is that the approach to manage the stock market will continue to be dribs-and-drabs of policy announcements: a ban on share sales here, a decrease in transaction fees there. Perhaps the markets would be better served by a faster collapse to more reasonable PE levels combined with better reporting and auditing on listed companies. Such a collapse could make China’s stock markets less like a casino for speculators and more like a tool for capital formation. That’s where the second official policy announcement may come in.

Before the huge rundown in the stock markets over the last few weeks, it had already been announced that the securities regulator would be moving to a more market-oriented, registration-based IPO system. Rather than being anointed and put in a queue, companies seeking to be listed would need to compete and produce records, audits, and prospectuses up to global investment-banking-quality levels. So let’s hope, but not predict, that the regulator will do this and not abandon or delay the registration-based listing system due to today’s adverse market conditions. Now, in fact, is the perfect time.

Source: Shanghai Forum, Jason Inch, 2016.